How can the actions of an individual change a system?

As always, we have a driving question that leads us through our projects, and we were tasked with this one. The material we covered was a continuation of our historic timeline and had landed us in the time of civil and political change, the 1950’s and 60’s.

In order to answer this question we were set up into pairs, and I was selected to be with Simon. Not going to lie I was extremely thankful for this because I’ve always been a much more literary person. I’m much better at writing, research, taking notes etc, whereas Simon’s editing, photography, and videography skills have lead to him creating videos outside of class and not just the ones mandated by school. While we were brainstorming video ideas we decided that we wanted one that connected back to the civil rights movement, the modern day, and Canada. This was a seemingly difficult task at first but we found one story that had an aspect of all three: Malala Yusafzai.

This was the final product that we created for the unit, so of course we need to talk about the key ideas that lead up to this point. As most units have with Ms Willemse, we were  yet again given a novel to read. Entitled Dear Martin, by Nic Stone, this book would perfectly encapsulate the topic of the unit to follow. Justyce McAllister is a student at the top of his grade 12 class and is Ivy League bound. He struggled with a rough childhood and despite leaving this neighbourhood behind, he can’t escape the hate of his old peers or the ridicule from his current high school classmates. With a whirlwind of questions of what to do, followed by an unjust police shooting of which his best friend was the victim, Justyce looks to the lessons of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He begins writing letters to MLK in hopes of some answers in order to help change and to cope. This novel holds all of our key ideas for the “We Shall Overcome” unit: racial inequality, the younger generation looking to make a change, and forcing a better future.

yet again given a novel to read. Entitled Dear Martin, by Nic Stone, this book would perfectly encapsulate the topic of the unit to follow. Justyce McAllister is a student at the top of his grade 12 class and is Ivy League bound. He struggled with a rough childhood and despite leaving this neighbourhood behind, he can’t escape the hate of his old peers or the ridicule from his current high school classmates. With a whirlwind of questions of what to do, followed by an unjust police shooting of which his best friend was the victim, Justyce looks to the lessons of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He begins writing letters to MLK in hopes of some answers in order to help change and to cope. This novel holds all of our key ideas for the “We Shall Overcome” unit: racial inequality, the younger generation looking to make a change, and forcing a better future.

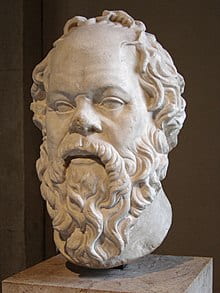

If you’ve studied any kind of Greek history, you’ll have heard of the philosopher Socrates. He created an idea for a group discussion which is now known as a Socratic Seminar, and are named such because they have a representation of Socrates’ belief in the power of questions, the importance of a challenging inquiry over information, and discussion instead of debate in order to gain a meaningful and in depth understanding of the text at hand. A proper Socratic seminar is a formal discussion where the leader asks an extremely open ended question from which a genial conversation would spark, however in our class this didn’t happen right away. Dear Martin, was the studied text for two out of four of our seminar’s. However, our class did change the style a little where we had an open floor policy in which everyone would participate and ask questions, but we were often stumped for topic material and would simply discuss the surface content.

When I didn’t have field hockey or a migraine and could actually attend these Socratic Seminars, I really enjoyed them. It was an extremely good opportunity to truly voice your opinion on any of the texts or relating issues. I personally found the movies much easier to discuss because not only could we relate images, but by taking thorough notes it was a lot easier to remember events that had occurred because it was in your own words. I find it much harder to simply highlight and then re-read. However, during these discussions it was sometimes hard to get ALL of your points across due to the amount of people attempting to contribute. Our class was divided into two groups, so there was approximately 7-9 people per seminar, and with that many students, who all had drastically different point of views, it was very difficult to voice every word you had in mind; and overall that was my only issue with these Socratic Seminars.

Although the novel study was a really great way to summarize the unit as a whole, the largest chunk of material we studied came directly from the Civil Rights Movment lead by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. However, we started studying this history way farther back on the timeline, beginning with the Emancipation Proclamaiton, and ending in 1968 after multiple assassinations and the election of President Nixon.

I think this is my favourite unit to date, and I was genuinely intrigued by all of the stories we discussed and read. However, a few stuck with me more than others:

While visiting family in the extremely racially divided Mississippi of 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till, an African American born and raised in Chicago, was brutally murdered for allegedly flirting with a white woman four days earlier by simply “wolf whistling” at her inside of her husband’s convenience store. His assailants—the white woman’s husband and her brother—made Emmett carry a 75-pound cotton-gin fan to the bank of the Tallahatchie River and ordered him to take off his clothes. The two men then beat him nearly to death, gouged out his eye, shot him in the head and then threw his body, tied to the cotton-gin fan with barbed wire, into the river.

All of this information hadn’t come to light until after the those responsible for Emmett’s death had gotten away with no charges while in front of an all white, all male jury. It wasn’t until later that they had brought these details forward and the truth of Till’s murder was sent out to the public. Many believe that this horrific act is what sparked the Civil Rights Movement because Emmett Till’s mother made the bold decision to put his open casket on display outside of their local church, and word along with photographs had soon spread across the nation. This public event truly brought the unfairness and inequality that the black community was dealing with at the time, and was something that they didn’t want to see happen again.

Freedom Riders were groups of white and African American civil rights activists who participated in Freedom Rides, bus trips through the American South in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals. Freedom Riders tried to use “whites-only” restrooms and lunch counters at bus stations in Alabama, South Carolina and other Southern states. The groups were confronted by arresting police officers—as well as horrific violence from white protestors—along their routes, but also drew international attention to their cause.

The first Freedom Ride took place on May 4th, 1961, when seven blacks and six whites left Washington D.C. on two public buses bound for the Deep South. In the first few days, the riders encountered only minor hostility, but in the second week the riders experienced severe beatings. Outside Anniston, Alabama, one fo their buses was bred and in once in Birmingham, several dozen white people attacked the rider only two blocks from the sheriff’s office. With the intervention of the U.S. Justice Department, most of CORE’s Freedom Riders were evacuated form Birmingham, Alabama to New Orleans. John Lewis, a former seminary student who would later lead SNCC and become a US congressman, stayed behind in Alabama.

The riders continued to Mississippi, where they endured further brutality and jail terms but generated more publicity and inspired dozens more Freedom Rides. By the end of the summer, the protests had spread to train stations and airports across the South, and in November, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued rules prohibiting segregated transportation facilities.

The March on Washington was a massive protest march that occurred in August 1963, when some 250,000 people gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Also known as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the event aimed to draw attention to continuing challenges and inequalities faced by African Americans a century after emancipation. It was also the occasion of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s now-iconic “I Have A Dream” speech.

In 1941, A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and an elder statesman of the civil rights movement, had planned a mass march on Washington to protest blacks’ exclusion from World War II defense jobs and New Deal programs. But a day before the event, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with Randolph and agreed to issue an executive order forbidding discrimination against workers in defense industries and government and establishing the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) to investigate charges of racial discrimination. In return, Randolph called off the planned march.

In the mid-1940s, Congress cut off funding to the FEPC, and it dissolved in 1946; it would be another 20 years before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) was formed to take on some of the same issues. Meanwhile, with the rise of the charismatic young civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. in the mid-1950s, Randolph proposed another mass march on Washington in 1957, hoping to capitalize on King’s appeal and harness the organizing power of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP). In May 1957, nearly 25,000 demonstrators gathered at the Lincoln Memorial to commemorate the third anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education ruling, and urge the federal government to follow through on its decision in the trial.

The Selma to Montgomery march was part of a series of civil-rights protests that occurred in 1965 in Alabama, a Southern state with deeply entrenched racist policies. In March of that year, in an effort to register black voters in the South, protesters marching the 54-mile route from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery were confronted with deadly violence from local authorities and white vigilante groups. As the world watched, the protesters—under the protection of federalized National Guard troops—finally achieved their goal, walking around the clock for three days to reach Montgomery. The historic march, and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s participation in it, raised awareness of the difficulties faced by black voters, and the need for a national Voting Rights Act.

Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade discrimination in voting on the basis of race, efforts by civil rights organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to register black voters met with fierce resistance in southern states such as Alabama. In early 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. and SCLC decided to make Selma, located in Dallas County, Alabama, the focus of a black voter registration campaign. King had won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, and his profile would help draw international attention to the events that followed. Alabama Governor George Wallace was a notorious opponent of desegregation, and the local county sheriff in Dallas County had led a steadfast opposition to black voter registration drives. As a result, only 2 percent of Selma’s eligible black voters (about 300 out of 15,000) had managed to register to vote.

Overall, the project lasted about two months. It was quite a jam packed unit but it was definitely one of the most interesting. By watching movies and interviews, it is much easier to analyze and discuss the topic because our class finds them much more engaging. In the past we have done many solo projects as well as group projects, and honestly I really enjoyed the partner work due to the easy distribution and balancing of skills. Not only do you get to do your part in all of the work, but it also requires you to learn all of the same material, instead of focusing on one single aspect like in a group project.

Be First to Comment